Tagged: frivolous

“[G]iven the large and growing number of IFP [in forma pauperis] petitions filed with the Court, this class of cases requires some form of systematic consideration. This article compares a sample of the unpaid petitions for review filed with the U.S. Supreme Court from the 1976 through 1985 terms to a similar sample of paid petitions to determine whether and how the two dockets differ. Examination of the cases indicates that the IFP petitions are not categorically frivolous and unimportant and suggests, as a result, that these petitions require further consideration in the literature on the Supreme Court’s agenda setting.”

Source: Wendy L. Watson. The U.S. Supreme Court’s In Forma Pauperis Docket: A Descriptive Analysis. The Justice System Journal, Vol. 27, No. 1. pg. 1. 2006.

read my Em. Motion for Reconsideration En Banc, or in the Alternative, Motion to Recall the Mandate Pending the Filing of a Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court

The Second Circuit rendered its decision on March 11, 2015. I received the Order in the mail on March 17, 2014 and pursuant to Fed. R. App. P. 40, the Motion for Reconsideration was due by March 25, 2014. I actually wrote this 15-page Motion in two days after I decided to scrap the Motion I was working on.

This case was destined to reach the Supreme Court, so I wasn’t too concerned about the decisions of the lower courts because I know for a fact that as a matter of law, I have proven my claims against William Morris, Loeb & Loeb LLP, Michael P. Zweig and others beyond a reasonable doubt.

In the end, it all works out because writing this Motion helped prepare me to write my petition for a writ of certiorari. If the Second Circuit is going to issue another 2 sentence Order falsely saying my appeal “lacks an arguable basis either in law or in fact,” then I asked them to issue their decision no later than April 1, 2015. I think that’s pretty reasonable since they aren’t upholding the law or discussing the facts of the case…or even providing an ethical judicial opinion which is required of an Article III federal judge in a case of this magnitude.

To Clarence and his racist white buddies in black robes on the bench: “I been waiting on [ya’ll] at the do’!” Lmao!!! (shout out to Ms. Foxy!!)

the Reply to my Motion for Extraordinary Relief is submitted to the 2nd Circuit!!!

Wow! I can’t believe that in four days, I was able to condense my discussion of the overall fraud that has been perpetrated upon the Court by Loeb & Loeb LLP and the Court itself, into those 10 pages!! What makes things even better, is that if the appellate court denies my Motion [without providing an ethical and objective judicial opinion], then this pleading can essentially serve as my petition for writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court.

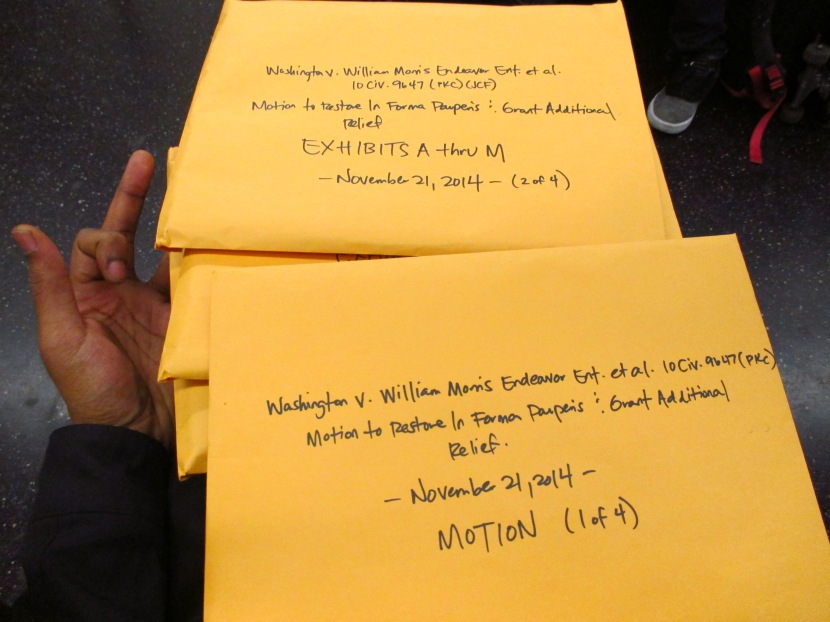

Below are some pix chronicling my day as I prepared to submit what could very well be the last pleading I submit to the Second Circuit:

Thank you GOD for always watching over me [and intervening while I was at the post office to prevent me from mailing Loeb & Loeb LLP the wrong version of the pleading]!!

“The Supreme Court’s decision in University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center v. Nassar[, 133 S. Ct. 2517 (2013)] represents a watershed moment in employment discrimination litigation. The majority opinion posited that an employee might try to avoid termination by filing a fake retaliation claim against his employer. It also expressed fears about courts, administrative agencies, and employers being subjected to floodgates of litigation. It then explicitly used these concerns about fakers and floodgates to tip substantive discrimination law in an employer-friendly direction.”

Nassar expresses three ideas about employees and their claims. First, the sheer volume of cases is enough to favor a more onerous causal standard. Second, enough employees will bring false claims that substantive retaliation doctrine needs to protect courts, administrative agencies, and employers from fakers. Third, existing procedural mechanisms are not adequate to ferret out these false claims. Rather, they must be dealt with by altering the substantive law.

This Article responds to the alleged fakers and floodgates problem. First, it argues that the Court has created reasons to alter the law that are not grounded in congressional intent. Title VII contains numerous provisions that limit the reach of the statute. Beyond these restrictions, Congress never expressed any intention to limit the number of claims heard by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) or the courts based on concerns about the sheer volume of such claims. Nor did Congress express any intent that the courts use the substantive law to screen for false retaliation cases. Through various provisions in Title VII, Congress established a statute designed to protect employers, employees, and courts. Multiple provisions establish a mechanism to ensure that employees are able to bring claims, that employers can adequately defend against claims, and that courts do not hear claims that can be resolved by the EEOC. Moreover, Title VII was enacted in the presence of several existing devices that can be employed to stem any false claims and any related floodgates of litigation. These devices allow judges to sanction parties who file false claims and to dismiss these cases. While the Supreme Court considers these devices to be adequate to handle the misbehavior of employers, in Nassar the Court rejected the possibility that procedural mechanisms are sufficient to deal with false claims filed by employees.

Second, although we argue that the Court’s fakers and floodgates arguments are improper, they are also problematic because they are not supported by empirical or other evidence. To the contrary, available evidence shows that the number of employment-related civil rights claims is decreasing both in raw numbers and in proportion to the number of civil claims filed in federal court.” This Article questions whether the judiciary generally, and the Supreme Court in particular, is the best institution to make factual claims about fakers and floodgates.

Third, this Article also challenges the accuracy of the Court’s assertion that changing the substantive law will reduce the number of spurious claims. At best, such a change is a blunt instrument for handling frivolous claims. Most importantly, changing the law represents a choice about what counts as legal retaliation and what does not. By requiring plaintiffs to establish but for cause, the Supreme Court has declared that an employer does not retaliate against an employee (in a legal sense) if the causal connection is less strong. In other words, if an employee can show only that retaliatory motive was a motivating factor in her termination, she has not suffered retaliation under Title VII.

Fourth, we discuss the dangers of the floodgates and fakers arguments becoming explicitly embedded in judicial doctrine. Such a default position distracts from the larger congressional goal of preventing retaliation and confuses the underlying legal doctrine. Thus far, two courts have already cited the Court’s concerns in their opinions. This Article calls for the EEOC and other organizations concerned with employment discrimination to develop a factual response to arguments about fakers and floodgates before these myths develop into an uncontestable judicial narrative that courts can use to justify other changes in the law.

Finally, we argue that the fakers and floodgates arguments are consistent with a broader problem-courts’ infusion of their own views of evidence of discrimination into procedure and substance. Courts use these devices to prevent juries from hearing factually intensive civil rights cases, even when a plaintiff presents evidence of a colorable claim. (emphasis added)

Smh…

Source: Sandra F. Sperino and Suja A. Thomas. Fakers and Floodgates. Stanford Journal of Civil Rights & Civil Liberties. pg. 223-225. June 2014.

submitted! thank you GOD!!!

There is the possibility that the Second Circuit will not restore my in forma pauperis status, so please donate to my Campaign 2 END RACISM — http://www.gofundme.com/campaign2endracism — so I can afford the costs to appeal the fraudulently procured decisions of Republican federal judge P. Kevin Castel in the Southern District of New York.

finally had the chance to read the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure. is my appeal “frivolous” or not? if it is, double the monetary damages owed to William Morris.

if certain companies are exempt from fully complying with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and claims of INTENTIONAL systemic disparate treatment & disparate impact cannot be raised, then say that so [pro se] plaintiffs like myself won’t waste time advancing “frivolous” legal theories to the facts of the case or be accused of engaging in bad faith when the finder of fact refuses to acknowledge the evidence in support of those claims over the course of 4 years…

“While a trial court has broad discretion in denying an application to proceed in forma pauperis under 28 U.S.C.A. § 1915, it must not act arbitrarily and it may not deny the application on erroneous grounds…”

Source: Pace v. Evans, 709 F.2d 1428 (11th Cir. 1983).

“When courts believe that most claims are frivolous, they will be far more concerned with false positives — wrongful accusations of discrimination — not false negatives that leave claims of discrimination unredressed.”

Source: Hon. Nancy Gertner and Elizabeth M. Schneider. “Only Procedural”: Thoughts on the Substantive Law Dimensions of Preliminary Procedural Decisions in Employment Discrimination Cases, 57 N.Y.L. Sch. L. Rev.767, 776 (2012–2013).

“Why are the federal courts so hostile to discrimination claims?”

Each year, the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts holds an extraordinary panel. All active judges are present to answer questions from the bar. A lawyer’s question one year was particularly provocative: “Why are the federal courts so hostile to discrimination claims?” One judge after another insisted that there was no hostility. All they were doing when they dismissed employment discrimination cases was following the law—nothing more, nothing less.

I disagreed. Federal courts, I believed, were hostile to discrimination cases. Although the judges may have thought they were entirely unbiased, the outcomes of those cases told a different story. The law judges felt “compelled” to apply had become increasingly problematic. Changes in substantive discrimination law since the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 were tantamount to a virtual repeal. This was so not because of Congress; it was because of judges.

Decades ago, law-and-society scholars offered an explanation for that phenomenon, evaluating the structural forces at work in law-reform litigation that lead to one-sided judicial outcomes. Focusing on employment discrimination claims, Marc Galanter argued that, because employers are “repeat players” whereas individual plaintiffs are not, the repeat players have every incentive to settle the strong cases and litigate the weak ones. Over time, strategic settlement practices produce judicial interpretations of rights that favor the repeat players’ interests. More recently, Catherine Albiston went further, identifying the specific opportunities for substantive rulemaking in this litigation—as in summary judgment and motions to dismiss—and how the “repeat players,” to use Galanter’s term, take advantage of them.

In this Essay, drawing on my seventeen years on the federal bench, I attempt to provide a firsthand and more detailed account of employment discrimination law’s skewed evolution—the phenomenon I call “Losers’ Rules.” I begin with a discussion of the wholly one-sided legal doctrines that characterize discrimination law. In effect, today’s plaintiff stands to lose unless he or she can prove that the defendant had explicitly discriminatory policies in place or that the relevant actors were overtly biased. It is hard to imagine a higher bar or one less consistent with the legal standards developed after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, let alone with the way discrimination manifests itself in the twenty-first century. Although ideology may have something to do with these changes, and indeed the bench may be far less supportive of antidiscrimination laws than it was during the years following the laws’ passage, I explore another explanation. Asymmetric decisionmaking—where judges are encouraged to write detailed decisions when granting summary judgment and not to write it—fundamentally changes the lens through which employment cases are viewed, in two respects. First, it encourages judges to see employment discrimination cases as trivial or frivolous, as decision after decision details why the plaintiff loses. And second, it leads to the development of decision heuristics—the Losers’ Rules—that serve to justify prodefendant outcomes and thereby exacerbate the one-sided development of the law.

Great article by Nancy Gertner [not a woman of color]. This is what happens when the federal courts have intentionally been filled with ideologically conservative, white male, Republican appointed federal judges, particularly since Ronald Reagan became president 34 years ago. Below is Gertner discussing this topic at the New York Law School’s Symposium titled “A View From the Bench — The Judges’ Perspective on Summary Judgment In Employment Discrimination Cases.” [go to the 38:38 mark]

Major reform is needed — not only to strengthen the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but to develop structural mechanisms that will eliminate racist and corrupt judges who intentionally ignore the law and deprive plaintiffs in employment discrimination cases of their right to a jury trial under the color of law.

Source: Nancy Gertner. “Loser’s Rules.” The Yale Law Journal Online. October 16, 2012. http://yalelawjournal.org/the-yale-law-journal-pocket-part/procedure/losers%E2%80%99-rules/